Sept. 9, 2011

Military heritage? You are sitting in it. This is Memorial Stadium. Since it was dedicated in 1942, this stadium commemorates all of Clemson’s sons (to this moment, no daughters) who have given their lives in the defense of their country. You are surrounded by it.

To the east and at the crest of the Hill stands Fort Hill House. Married there were Thomas Green Clemson and Anna Maria Calhoun. Although a revolution (successful) in France may not count, Tom Clemson, or “Giraffe” as he was called by his classmates at the Royal School of Mines (Paris), fought for “liberty” in the French Revolution of 1830.

He later served in the Trans-Mississippi Company in the Civil War. Born in the house was his son, who also was in the Confederate Army. Years later, Mr. Clemson, a widower and a father whose four children had already died, asked three people (two of whom were friends of his) to spend a day with him at Fort Hill to help him decide how best to create the school that Mrs. Clemson and he wanted for the people of South Carolina. Two of those men were also veterans…one, Daniel Keating Norris, had been wounded at the age of 19 and the other, Richard Wright Simpson, was taken ill by camp disease.

Their plan, called The Will, which was written by the veteran-lawyer Simpson, called for seven life trustees. Mr. Clemson, with Simpson’s help, chose the initial seven. Five of those men were veterans. Eventually, the South Carolina Legislature chose six more trustees. Several of those were veterans.

Part of their business was to choose the new faculty. The man they chose for president, Henry Aubrey Strode, enlisted at the age of 16 and fought at Gettysburg. Chemistry professor Mark Bernard Hardin had been in the artillery and English literature professor Charles Manning Furman served in the infantry.

The first 442 students (it was the second-largest institution in South Carolina, with Claflin College being the largest) dressed in their West Point gray-wool uniforms on the seventh day of July (note the season of the year and the mode of dress). For the next 71 years, the sons of “dear old Clemson” drilled in the sun and snow while they learned trigonometry, calculus, chemistry, and history from their warrior teachers. When the nation called, the sons of Clemson went. Seven (at least) went to the Spanish American War, and they all came back.

When President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on the Second German Empire in 1917, a senior moved that the senior class present itself to the President as “ready for duty.” Although instructed to await orders, half were gone by graduation, leaving their parents to receive their diplomas granted by the faculty with permission of the trustees. A total of 698 (at least) served and 27 died. Two received the Congressional Medal of Honor. One died in Nicaragua in inter-war military action there.

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared war on the Germans, Japanese, Italians, and their allies in 1941, one Clemson alumnus had already died, shot down over the English Channel fighting for “God, King, & Country” during the German “blitz” of Britain. In all, 376 of Clemson’s sons died in that war out of the 5,000 who served around the world. One received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Not included in that total were the faculty, some 105 out of about 300, who also answered their nation’s call. Some were in defense-related research in Britain, Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., and other places. Others were in language schools preparing for occupation. But others were on front lines, some wounded and some captured.

When peace came, they (or many of them) returned to their classrooms. Many have died now and some are buried in the cemetery that lies just to the south of this memorial. Think of them as you tailgate. Many others have joined their mothers, fathers, and children in old cemeteries such as Old Stone Church. Remember them as you rush by on Highway 76 on the way home from the game.

But the enemies of “liberty” could not be restrained. The Korean conflict erupted and 18 died. During the Cuban Missile crisis, another son of Clemson died, the only American death. Then Vietnam claimed the lives of 29 more. I can still see two of them, one industrious with his nose in his book and the other infectiously friendly, now both dead. The Cold War called 23 away forever. And this latest series of conflicts, mainly in the Persian Gulf, still three more.

To the west stands Jervey Athletic Center. It honors one of Clemson’s greats, Frank Jervey, who was nearly left for dead in France in World War I. And next to it, the McFadden Building calls to mind a two-time All-American who served in World War II.

So many of the names of Clemson, the streets, the dormitories, and the classroom buildings (especially the classroom buildings) remember those who sacrificed or who willingly offered their lives for liberty, for freedom, and for us. Give thanks and remember.

Duke

Duke

Florida State

Florida State  Louisville

Louisville  Furman

Furman  South Carolina

South Carolina  LSU

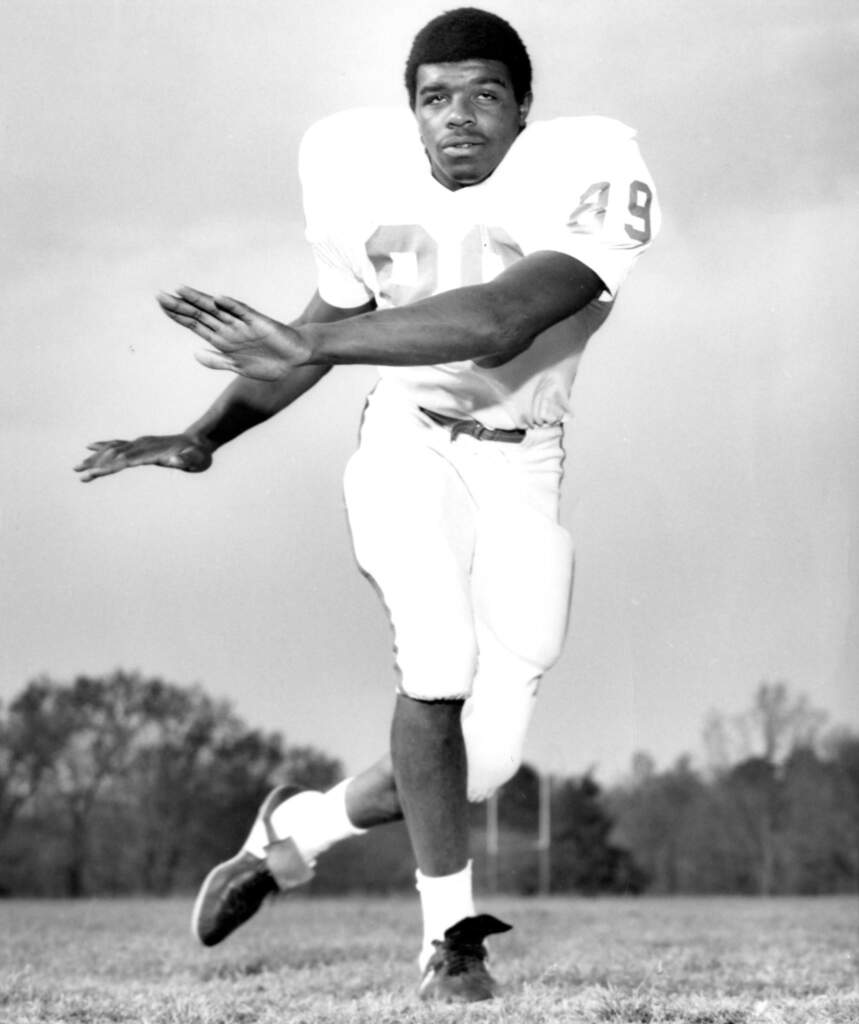

LSU  Troy

Troy  Georgia Tech

Georgia Tech  Syracuse

Syracuse  North Carolina

North Carolina  Boston College

Boston College  SMU

SMU