By William Qualkinbush

Symbols are everywhere. They are easy to find and hard to identify because they represent something unique outside of themselves. Anything can be a symbol, but no symbol is exactly the same for two people. Each one is essentially an image within an image, a memento that can take a person back in time to an event marked with a memory that is specific to him or her alone.

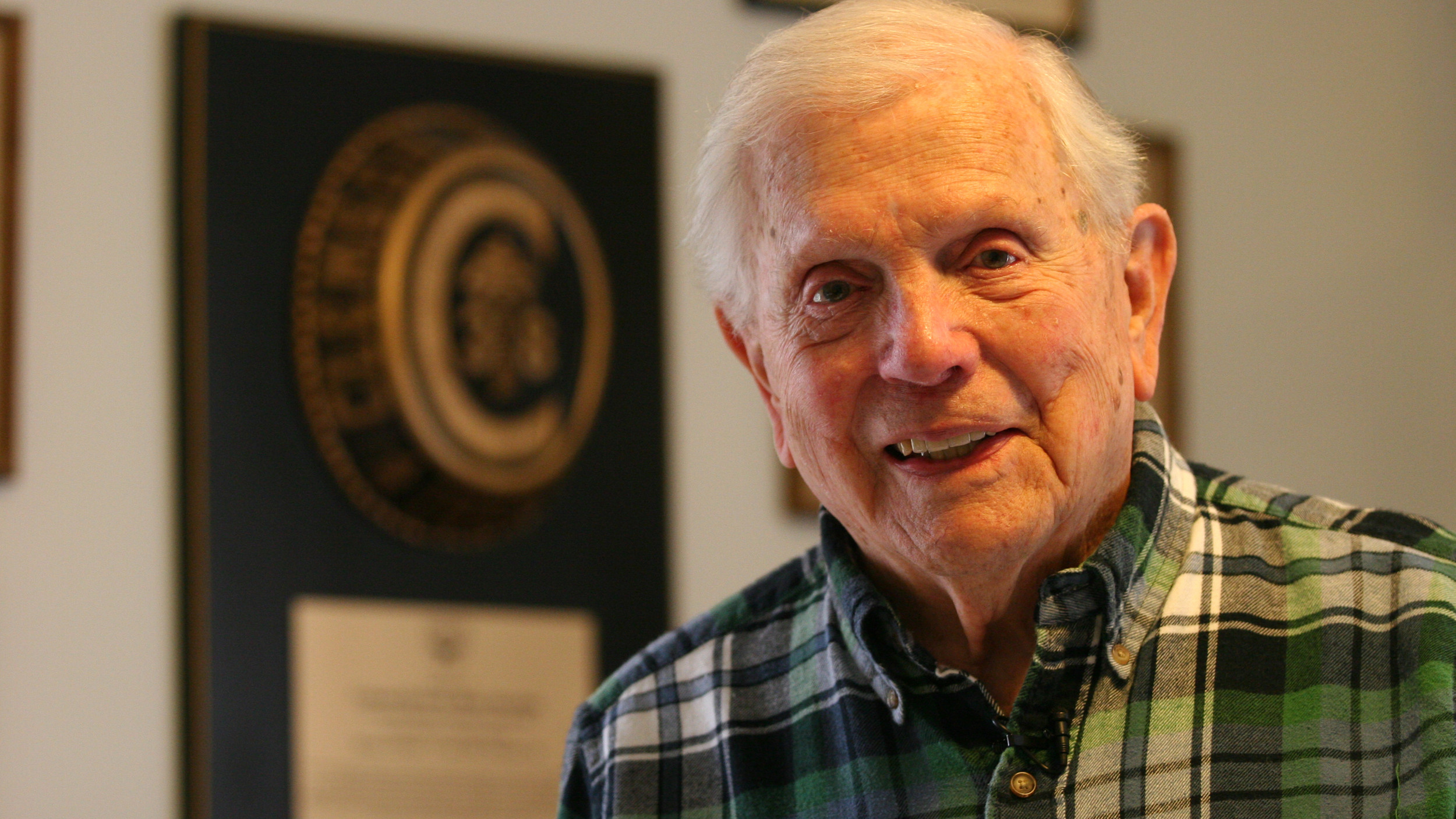

Things are symbols, but the absence of something can be symbolic as well. For retired Col. Ben Skardon, it is what he no longer has that defines his past and present. In fact, it is because of that symbol he is alive to tell his story today…at a spry 95 years of age.

Skardon is a 1938 Clemson graduate who would go on to a decorated career of military service. Growing up, he considered four occupations to be higher callings…law, medicine, ministry, and the military. The son of an Episcopalian minister, Skardon said he always favored the military route and used Clemson as an avenue to get there.

As he looks at what Clemson University has become today, Skardon still sees the paths he walked as he looks past the development that has taken place over time to a different era in the foothills.

“It’s hard for me not to think about it as a military school,” he said. “That’s all I knew about Clemson College.”

Skardon’s training at Clemson was of the highest quality, but it could not possibly have prepared him for all of the challenges and pitfalls that he would face stationed in the Philippines during World War II.

An illness delayed Skardon’s commission upon graduation, but he eventually went on active duty a little over a year after he left Clemson. Two years later, the United States was at war, and Skardon was sent to the front lines of battle.

Two months after Skardon began his tour of duty in Manila, Philippines, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Skardon was immediately thrust into the throes of war on the Pacific front, as he and his comrades joined forces with the Filipino army to combat the Japanese at the Battle of Bataan.

After three months of fighting, the Allied forces surrendered to the Japanese. Tens of thousands of American and Filipino soldiers, including Skardon, were now prisoners of war.

The Japanese attempted to move the POWs to a special encampment 65 miles away. They divided the prisoners into groups and marched them on what is now infamously known as the “Bataan Death March.”

The treatment of Skardon and his comrades was deplorable. People were killed for falling behind or attempting to escape. Very little food or water was provided as the starving soldiers were paraded south.

Being imprisoned is devastating enough, but Skardon was already suffering from dehydration and starvation due to the length of the battle he and those who fought alongside him waged. The combination made it a nearly impossible task.

However, Skardon persevered. He credited the ability to make it through the excruciating march to survival, loyalty, and faith, all tenets he has held dear since his childhood.

“Survival has a lot to do with attitude, an attitude that says, ‘I’m still alive, I have to keep going’,” said Skardon. “I lived off of that because there was no physical reason for me to survive the ‘Bataan Death March’ by any manner or means.”

Skardon’s health worsened once he reached his destination. Just getting there was difficult enough, but food and water were still scarce, and disease was rampant among the prisoners of war.

For the next three-plus years, Skardon fought against the odds to see each successive day. He had a number of bouts with diseases related to dehydration and malnutrition, including malaria. His eyes were clamped shut due to an infection and the soles of his feet were swollen and infected.

“That’s the only time I ever felt that way,” recalled Skardon. “I think that’s the closest my body ever came to shutting down.”

It was at his lowest point that two of Skardon’s fellow prisoners began to take his life into their hands. Concerned that Skardon might be taken away by his Japanese captors and left to die, Henry Leitner and Otis Morgan, both Clemson graduates, began to feed and bathe him to make sure he maintained.

It was during these bouts of sickness that Skardon contemplated giving up and surrendering his body, just as the Army had surrendered at Bataan. But his friends who were going through similar circumstances lifted him up.

For them, it was all about survival, Skardon said. No matter what, staying alive was the most important thing for all of them. In a way, life became driven by instinct, rendering many elements of basic training invalid.

“When you have to learn everything from the ground up and everything else you have came out of books, they don’t jive,” said Skardon. “You’ll take any measure necessary to accomplish your mission, but it won’t be by the book.”

Skardon and his friends took the measures they had to take to live day-to-day, which is where Clemson University and symbols enter the picture.

As most of the personal belongings of the prisoners had been confiscated, Skardon managed to hide his Clemson ring. As conditions worsened, the trio decided to trade the ring for sustenance.

Once the Japanese guards heard about a gold ring for sale in exchange for some food, they made the deal. Skardon, Leitner, and Morgan received potted ham and a live chicken in the swap.

As Leitner and Morgan used the food to care for Skardon, his health improved to the point that he was able to function on his own for the remainder of his time in captivity.

Leitner and Morgan both died as prisoners of war before the final surrender of Japanese troops in 1945. Skardon survived, eternally grateful for the friendship of the two men who saved his life so he could share his story.

Survival, loyalty, and faith are Skardon’s lifeblood. They are the principles that characterized his ability to persevere for three years in an enemy encampment. As hundreds and thousands of others around him suffered, bled, and died, Skardon’s Clemson ring allowed him to fight another day.

Clemson graduates of many generations display their rings with pride. They are identifiers that allow alumni to forge a connection as total strangers.

Skardon no longer has his original ring, but the symbolism of its absence is just as strong, if not stronger, than any others. He traded his Clemson ring for life in the face of death, which makes the story of his ring stand the test of time.

A person may not see Skardon’s ring on his finger, but anyone lucky enough to meet him today can clearly see its influence at work.

Pitt

Pitt  North Carolina

North Carolina  Elon

Elon  SMU

SMU  Syracuse

Syracuse  Alabama

Alabama  Tennessee

Tennessee  Charlotte

Charlotte  USC Upstate

USC Upstate  Ohio State

Ohio State  Georgia State`

Georgia State`  Ohio University

Ohio University  Virginia Tech

Virginia Tech  Indiana

Indiana  South Carolina

South Carolina  South Carolina

South Carolina  Campbell

Campbell  UAB

UAB  East Tennessee State

East Tennessee State  LSU

LSU  South Carolina

South Carolina  App State

App State  North Carolina A&T

North Carolina A&T  Charlotte

Charlotte  Troy

Troy  Georgia

Georgia  VCU

VCU  Georgia

Georgia  Stanford

Stanford  USC Upstate

USC Upstate  Georgia Tech

Georgia Tech  Wofford

Wofford  California

California  Queens

Queens  Georgetown

Georgetown  Norfolk State

Norfolk State  Louisville

Louisville  Charleston Southern

Charleston Southern  Syracuse

Syracuse  Virginia

Virginia  Florida State

Florida State  Wake Forest

Wake Forest  Miami (Fla.)

Miami (Fla.)  Notre Dame

Notre Dame